A Preventable Tragedy

In 2018, the Hart Cluett Museum received a large collection of photographs from the collection of H. Irving Moore and his son Robert Moore.

H. Irving Moore, Troy City Historian who died in 1986, was for many, many years an avid collector of all things related to Troy and Lansingburgh, and author of several books on their history. His son Robert, who died in 2018, continued to collect Troy photos. Robert’s brother Eric Moore donated the collection.

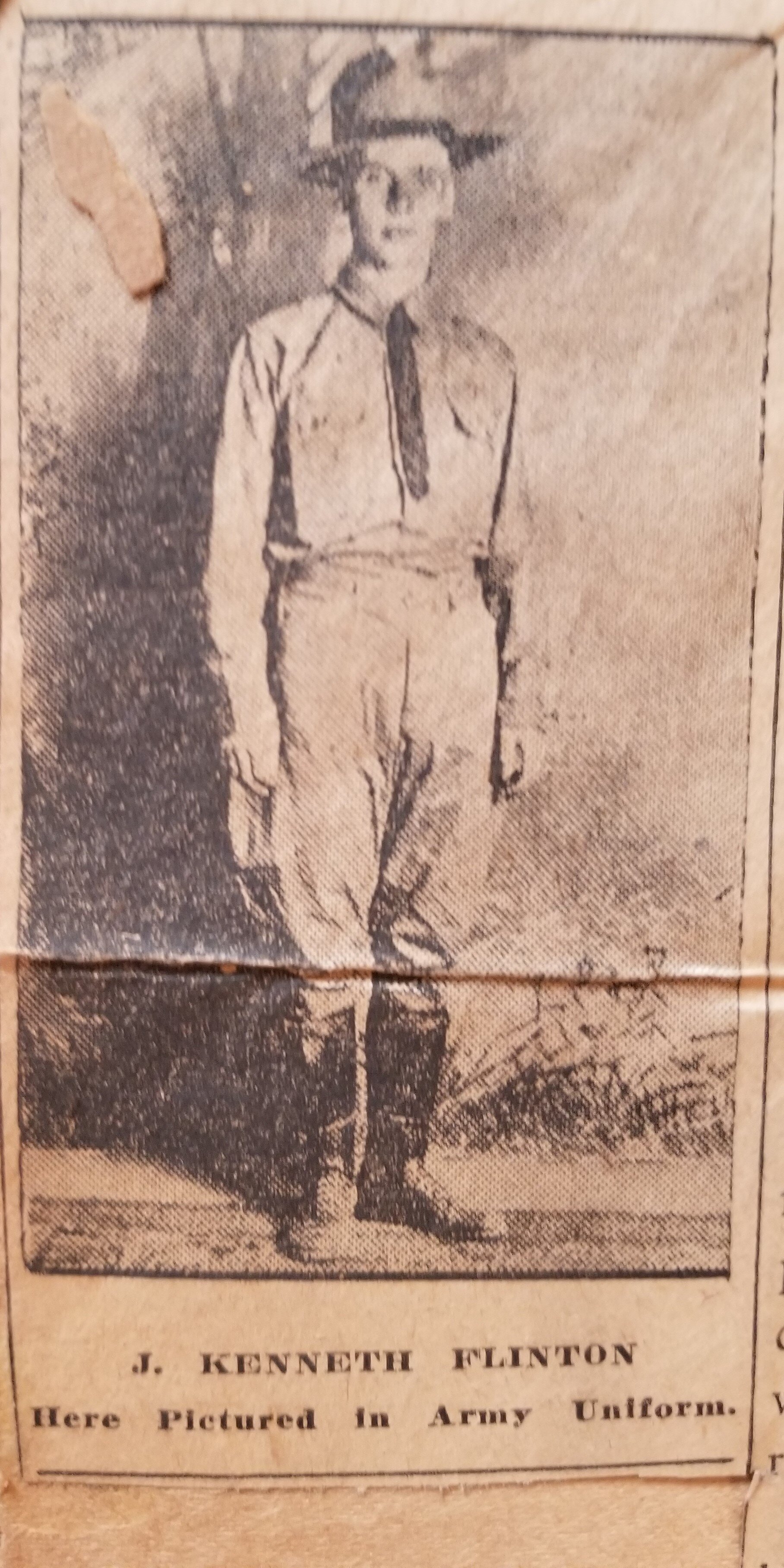

Amid all the photos was an envelope containing the extremely yellowed and brittle pages of what had been a single-topic scrapbook of newspaper clippings about the tragic death of Kenneth J. Flinton. Besides telling a sad story, they also illustrate the difficulty of trying to establish the facts of an incident solely from reading the newspaper, even when the intention was the straight reporting of events. For example, many of the articles call the victim “T. Kenneth Flinton,” but the name on his tombstone is Joseph K. Flinton - the K. for Kenneth.

Flinton was born in Lansingburgh in 1898, the son of Matthew and Clara Flinton. Records show that he enlisted in the U. S. Army on April 24, 1917, days after the U.S. declared war on Germany. He was posted to Fort Ethan Allen in Vermont, but suffered some sort of injury which made him unable to be in a front line unit. He served in the Medical Department of a unit based in Texas until discharge at the end of 1918. The newspaper reported incorrectly that he was in the Cavalry at Ft. Ethan Allen and the Air Service at Kelly Field in Texas.

Returning home to Troy after the war, Flinton became a Troy fireman. He married Alice Reilly in 1920 and they lived on Rensselaer Street in North Central Troy. Though Flinton’s job with the fire department was “chauffeur,” or driver, he did not hold back from fighting fires. In July 1928, a horse barn on the Burden Estate was on fire. Kenneth swam the Wynantskill Creek with a hose line to get water on the fire.

Much as they do now, the Troy Fire Department celebrated the annual Fire Prevention Week with public activities. In 1927, they had added a demonstration of their new nets, designed for victims to jump into from a burning building. Flinton had jumped from a second story window at the Stanley building, (now Hatchet Hardware) at the corner of State and 3rd Street, into a net held by his fellow firemen. Perhaps they wanted to make the 1928 event a bit more exciting, as on October 11 that year, Flinton made the jump again, this time from a 3rd story window. Sixteen of his fellow firemen held the net. The first newspaper story about the event said that there were 200 spectators, the second that there were 2000! Whichever the case, a number of people witnessed what everyone agreed was a perfect jump. Flinton landed seated, but the net immediately split, so that his head hit the sidewalk. He “lay in an inert mass.” His 19-year-old brother was in the crowd and was at his side in an instant, but Flinton never regained consciousness and died in the hospital that night.

The newspaper article which reported 2000 spectators added that “panic prevailed” among them. More than a dozen women fainted, including Mrs. Flinton, who was also in the crowd. Apparently their daughter Doris, aged six, was at a friend’s house.

The reaction to this tragedy was much as it would be today. First, why had the net failed? The Fire Department immediately stated that they had a number of these nets, manufactured by the Cory-Patterson Manufacturing Company in Ohio, and that they were both inspected and tested frequently. This company was the major manufacturer of safety nets in the U.S., beginning around 1910. The usual means of testing was to have young boys jump off a hose tower into them. (The canvas hoses of the era could rot if not dried thoroughly and were hung from towers for that purpose. The towers were often part of the fire station building.) The nets were supposed to support the weight of a grown man jumping from that height, but it was felt that perhaps Flinton should have jumped from the 2nd floor. A professor from R.P.I. was called in to inspect the fabric. When the net company was contacted, it was apparently out of business. As too often happens, the result of all this research was never reported in the newspaper. There was also no mention of lawsuits- which would have been inevitable today.

Second, there was a funeral to arrange. 85 firemen were arrayed on either side of the funeral procession, including a military escort from the local 105th Infantry Regiment. Flinton’s casket was transported from his home to St. Patrick’s Church and on to Oakwood Cemetery. Troy city offices were closed for the day so that employees could attend the funeral. A plane circled the grave, dropping flowers. The 105th NY Infantry Regiment fired a final salute.

Third, there was monetary relief for the widow. After the funeral, Proctor’s Theatre organized a vaudeville show, with all proceeds going to her. There were also many donations to a fund for the widow, all listed in the newspaper, day by day. The Troy Fireman’s Pension Fund awarded her a $25 per month pension. In 1934, Alice remarried, to Edward Konen, a truck driver.

The long-lasting result of the accident was that the Troy Fire Department tested its nets and training more closely, making changes necessary to save lives in the future.