The Farrell Letters

Thomas Farrell, drum major of the 2nd NY Volunteer Infantry Regiment

Descendants of Thomas Farrell recently donated five of his letters to the Hart-Cluett. They were written to his mom and dad at home in South Troy during the Civil War, along with information about the family. Thomas was the brother of the donor’s father’s grandmother, Ellen Farrell Halpin.

Thomas Farrell was born in 1843 in New Jersey, the son of Irish immigrants James and Mary Farrell. The 1860 US Census listed the family living in the 9th Ward. James, 45, was a laborer with real estate worth $700. He and Mary, 41, had children Thomas, 17, a carpenter; Timothy, 14; Helen, 5; and Margaret, 3.

When the Civil War began in April 1861, there was a great race to try to enlist the first New York Regiment- the Troy regiment was close, but was numbered the 2nd, when it was mustered into service on May 14, 1861. The regiment, under Colonel Joseph Carr, left for Virgina on May 23. They were based at Fortress Monroe and Newport News, participating on the edges of battles at Fair Oaks, Malvern Hill, Bristoe Station, the 2nd Bull Run, and Fredericksburg, before finishing their two years of service at the battle of Chancellorsville from April 30 to May 6, 1863. They returned to Troy having lost under 100 men killed, wounded, and missing during the two years, a very low total compared to regiments which served later in the war, but very significant to the families of those who died. The city of Troy greeted the soldiers with acclamation and a big parade.

Thomas Farrell enlisted April 29, 1861, aged 19, to serve two years. He was a musician. Early Civil War regiments had full military bands. The size of the band was reduced over time, but all regiments had a group of drummers and a few fifers, needed to help the troops march and to signal during battle. Thomas was promoted to Drum Major in October 1861, reduced in rank briefly, but then promoted to Corporal on November 1, 1862 and Sergeant just a month later. This change in title means he left the band to become an infantryman. He mustered out with the regiment at Troy on May 26, 1863.

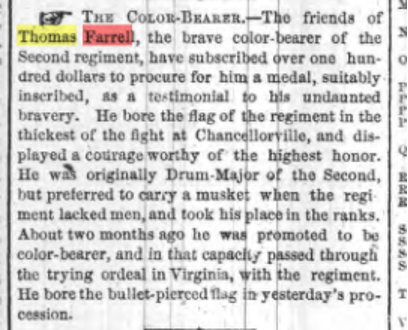

Troy Daily Times May 15, 1863

An article in the Troy “Daily Times” on May 15, 1863 fleshes out this bare recitation: “He was originally Drum-Major of the Second, but preferred to carry a musket when the regiment lacked men, and took his place in the ranks. About two months ago he was promoted to be color-bearer, and in that capacity passed through” the battle of Chancellorsville. Each regiment had its own flag, which was carried into battle. Of course the man carrying the flag was a prominent target , so noted for his bravery.

As a result of Farrell’s courage in the battle, his friends “subscribed over one hundred dollars to procure for him a medal…” In the end, the friends purchased “a magnificent gold watch” from “Cusack the jeweller” (sic) in Troy, engraved with his name and the names and dates of his battles. Farrell was presented with the watch at the Troy House, a prominent local tavern, where “he very modestly received it, bowed his acknowledgement, and retired.”

The five letters which Farrell wrote home to his family were addressed to the “corner of 3rd & 4th Sts., South Troy.” They are beautifully written and spelled, with a near total lack of punctuation, typical of the time. They include a few personal notes: Farrell needs some more stamps, he enjoys some of the publications his family sends him, he comments on some of the news of home, he wonders if they have seen Bridget Clough as she has stopped writing to him- but they shouldn’t mention this to anyone.

The letters also have some typical soldiers’ complaints: they have not been paid, they just got their camp set up and had to move, the officers are mean, the troops began a march which got bogged down in the mud. They confirm Farrell’s talent for music: he paid $2.50 to buy a flute, as he thought it would be a good way to pass the time. He noted that some peers felt he got the Drum Major’s job as he was a musical Irishman.

They also reveal that there was a good deal of discontent in the regiment over just how much time the men had enlisted for. Most of the men had enlisted for two years, but there were a few three-month men. Naturally, rumors spread about who was who, and in August 1861 a mutiny brewed, with men stacking their arms (muskets) and refusing to serve.

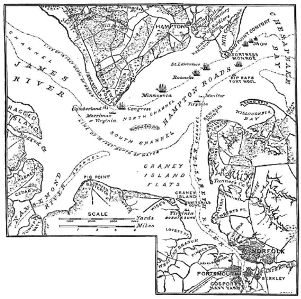

And one of the letters was written March 10, 1862, just after the epic and history-making battles between the Confederate iron-clad ship, the “Merrimac”, and the Union’s “Monitor”, called by Farrell the “Ericsson”, after John Ericsson, the inventor. The 2nd Infantry was based right at Newport News, on the James River, and had a perfect view of the naval battles. *

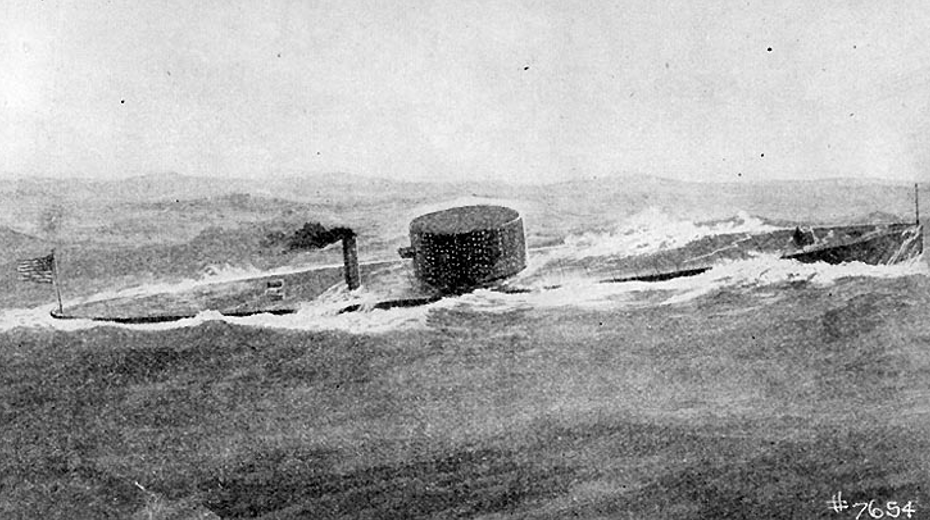

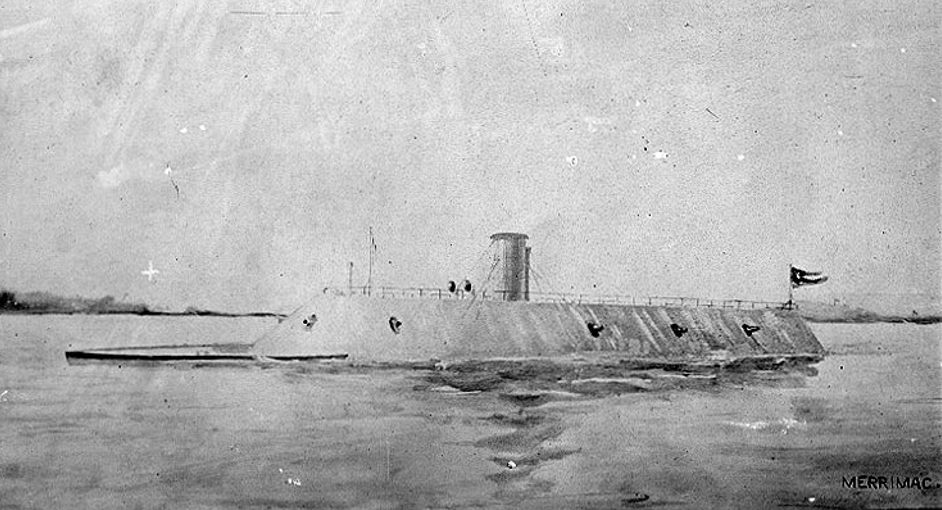

The battle was in two parts. First, on March 8, the Confederate “Merrimac”, as Farrell called her, or “CSS Virginia”, was a wooden ship clad in metal. There has been a lot written about this battle, but let’s use Farrell’s own words: (punctuation and capitalization added)

Map from Wikipedia. The 2nd NY was at Newport News, so had a ringside seat of the battle.

“The rebel iron boat the Merrimac… came out from Norfolk on Saturday at noon and came towards our two man of wars, the Congress and Cumberland. .. I heard tell of Infernal machines but never saw one till I saw her… We could see the Congress fate sealed. She came close up to the side of our vessel and there commenced to pour shot and shell mowing down the men on our boat. Our firing had no effect on her, she covered all over with iron rails. She had on her front a battering ram that when she run against our vessel she would smash her side to pieces. She was shaped like the roof of a house… After she knocked the Congress to pieces she steamed towards the Cumberland. When within a few feet of her she drove her battering ram with full force completely smashing in her side. The Cumberland poured her shot & shell into her but doing no good. The balls would glance off the Merrimac…. After 15 minutes work the Merrimac left her to her fate and then commenced to shell us in the camp…” As the “Cumberland” sank, Farrell could hear the cries of her sailors as they went to their deaths.

The next day, the Union iron clad, the “Monitor”, or as Farrell called her “the Ericsson”, took on the “Merrimac.” Though historians have paid much more attention to that battle than the first, Farrell disposes of it in a couple of sentences. “The two boats closed in to each other and such a banging as they gave each other yesterday.” Perhaps he was distracted as an alarm sounded that the Rebels were advancing toward the Union camp and “the men were throwing up entrenchments all last night and are working still.”

As mentioned above, Farrell finished his military career in gallant fashion, carrying the colors in the battle of Chancellorsville, one of the major battles of the war. He came back to a rapturous welcome for the Regiment by the city of Troy, and the presentation to him alone of that valuable and beautiful watch. Presumably Farrell would settle down to find a job, get reacquainted with friends and family, get married….but instead he contracted consumption (tuberculosis) and died June 30, 1864. The entry in the Interment Records of the city of Troy reports that he lived on the Greenbush Road, had had consumption for three months, and was treated by Dr. T.C. Brinsmade. Farrell was a laborer. He was buried at St. Joseph’s Cemetery, and was aged 21 years, 8 months, and 10 days at his death.

Musician Henry A Hoffman of the 124th NY Infantry Regiment- Certainly Thomas Farrell’s uniform would have been very similar. Library of Congress photo.

*Of course the “Monitor” had a very close connection to Troy. Its iron plates were rolled at John Griswold’s Rensselaer Iron Works in South Troy.